Director and producer Matt Tyrnauer’s new film, Citizen Jane: Battle for the City , shines a long overdue spotlight on the pioneering work of urban planning author and activist Jane Jacobs. The movie opens theatrically on April 21 in New York City and April 28 in Los Angeles before rolling out across the country. In advance of its Gotham bow, Architectural Digest ’s West Coast Editor Mayer Rus sat down with Tyrnauer over corned beef and kasha varnishkes at Canter's Deli in Los Angeles to discuss Jacobs’s heroic struggle to save the soul of New York, her repudiation of modernist orthodoxy, and the relevance of her resistance strategies in the context of America’s current political landscape.

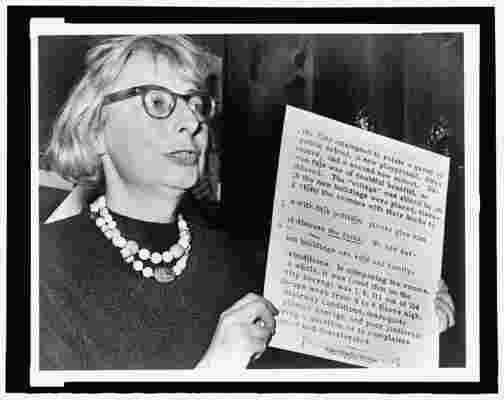

An image of the writer and activist, Jane Jacobs.

Mayer Rus: Your first movie was a documentary on the great Italian couturier Valentino . Your next movie is about Scotty Bowers, the infamous pimp-to-the-stars who ran a prostitution ring in Hollywood in the 1940s and ’50s. Glamour and sex—two great tastes that taste great together. But the subject of your new film, Citizen Jane , is less, um, flashy. Why did you want to make this movie?

Matthew Tyrnauer: I’m obsessed with architecture, design, cities. Jane Jacobs was an incredibly important figure, someone who transformed the way we look at cities—how we build and how we live. But most people don’t know who she is or what she accomplished. She wrote an immortal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities , which was published in 1961. It’s never been out of print, and it’s never been the subject of a documentary.

MR: A champion for enlightened urban planning seems like an arcane subject, difficult to dramatize. How did you approach the story?

MT: I wanted to tell the story in an accessible way, which is tricky for a movie about urbanism, architecture, and cities. Movies on those subjects tend to preach to the converted, or they end up in the library of the urban studies department, gathering dust on the shelf. One of Jane Jacobs’s signal accomplishments was to demystify the subject of urbanism by writing about it in a very plainspoken but powerful way. Her message was and is a populist message, so it seemed ridiculous to make a movie for academics.

MR: So how did you make it accessible?

MT: I made the movie as a character-driven story, with Jane Jacobs pitted against Robert Moses, the incredibly powerful New York urban planner, who had a kind of autocratic authority that no unelected official in this country ever had, before or since. Moses’s greatest antagonist in city life was Jane Jacobs, yet she’s not even mentioned in Robert Caro’s biography of Moses, The Power Broker , which runs 1,000-plus pages. My movie is about the power struggle between two people who each believed they were saving New York City, even though they had diametrically opposed points of view and methodologies.

MR: How do you set the stage for the conflict?

MT: After World War II, the same people in the U.S. who won the war through top-down, command-and-control military management decided to train their expertise on the decaying American city. They believed in the heroic modernist ideals and radical vision of Le Corbusier , which involved tearing down old cities and starting from scratch. This was a very sexy idea at the time—clean, comfortable homes for the masses instead of crime-ridden slums. It all looked great on paper, but it was a huge disaster. Robert Moses was destroying vital neighborhoods all around New York City to build his freeways and his massive blocks of public housing.

MR: And along comes Jane Jacobs.

MT: Yes, this relatively obscure journalist named Jane Jacobs, who had an associate editor’s position at Architectural Forum magazine. In her early writings, she was all for the kind of urban renewal espoused by Moses and his circle. She drank the Kool-Aid. But as Moses’s great master plans were implemented, it became clear that these were, in fact, very bad ideas. And Jane Jacobs stood up and said so, loudly. She spoke truth to power, and she helped bring down Robert Moses.

An image of Robert Moses, a city planner who primarily worked New York City. Here, Moses stands next to a model of his proposed Battery Bridge.

MR: You mentioned Le Corbusier earlier. The modernist revolution he spawned does not come off very favorably in your story.

MT: You could argue that Jane Jacobs was the anti-Corbusier. He was a visionary, and his futuristic conception of urban planning captured a lot of people’s imaginations, especially as an antidote to the poverty and overcrowding of the late industrial revolution. But he was conjuring his avant-garde visions from an ivory tower in Europe, totally divorced from the realities of the street. Corbusier’s disciples were Jewish academics who were driven out of Germany and installed for the most part at Harvard’s architecture school, where they became the most important voices of urbanism in this country. Their influence on the shape of our cities was vast. Corbusier, incidentally, looked down on the United States and could never stand to be here because we were always perverting his pristine plans and compromising.

MR: So Jacobs’s beef was not just with Moses but with Corbusier and his vision of gleaming homogeneity?

MT: Talk about going up against a sacred cow! Jane Jacobs realized that Le Corbusier’s theoretical approach would have disastrous effects in execution, particularly for what we think of as the inner cities. She almost single-handedly took on the architectural-industrial complex that defined the period of so-called urban renewal. She was the lone voice in the wilderness, screaming about these issues in print for a decade before she wrote her defining book and began to get some notice.

MR: Her work really changed the meaning of urban renewal, which didn’t always have the negative connotations and baggage it does today.

MT: In the words of James Baldwin, “Urban renewal means Negro removal.” Urban renewal was used as a blunt instrument against minorities, who tended to live in cities by mid-century. It was a device to marginalize minority citizens. At that time, respectable white people were supposed to be moving out to the suburbs. All of this was very bureaucratically manipulated, and it did a great deal of harm not only to the physical city but also the urban fabric and the social contract.

MR: All of this seems eerily familiar, especially in the context of the current political morass.

MT: Citizen Jane had its New York festival debut two days after the election last November, and the resonance was unmistakable. Then, in the wake of Trump’s inauguration and all the women-driven marches across the country, you realize that Jane Jacobs really invented the playbook on modern protest movements. All of that credit goes to her. And she actually won. She beat the system.

MR: What do you think she’d make of New York City in 2017?

MT: She would be appalled. The collusion between government agencies and private developers and other monied forces is the bête noir of her story. Let’s bring it back to our current president, a real estate developer who speaks relatively optimistically about infrastructure. Beware! Developers have a very good reason to be excited about infrastructure, because they make a lot of money on infrastructure. But are the things they’re pushing to build actually good for the people who live in the cities? Frequently, the answer is no. If you want to know the reasons why, see this movie.

MR: And yet there’s no prescription that emerges at the end of your picture.

MT: Jane Jacobs was militantly anti-prescriptive. She understood that every place, every street, and every community is different and therefore has different needs. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. What the movie tells you—and I hope empowers you to do—is to start to look around and understand the fundamental forces that affect the places that you live and the reasons why things are the way they are. You can’t make any real change without understanding those forces. This was Jacobs’s great gift to all of us. She was a skeptic who taught us how to look and see the city for all of its miraculous diversity.

Leave a Reply