When Italian architect Ettore Sottsass launched the controversial collection of furnishings known as Memphis at the Milan Furniture Fair in 1981, the design world was shocked. “It appalled some and amused others but put everyone attending the fair in a state of high excitement,” Suzanne Slesin wrote in The New York Times after the debut of the colorful, photogenic pieces designed by Sottsass and a group of young talents including Alessandro Mendini, Michele De Lucchi, and Nathalie Du Pasquier. Seemingly overnight, the extravagant furnishings flew into the private collections of David Bowie, Karl Lagerfeld, and other international tastemakers. Suddenly, Sottsass—then 64 years old and more than three decades into his career—became synonymous with the radical Memphis ethos and the movement’s poster child, his ecstatic, anthropomorphic Carlton room divider.

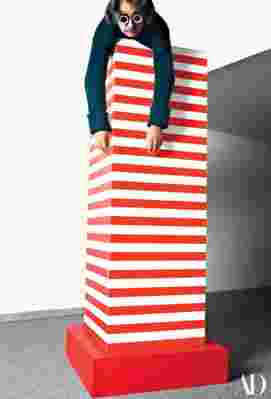

Ettore Sottsass flopping across the top of a laminate-covered-plywood superbox, designed in 1966 for Poltronova.

Sottsass hated it. “The fear of being stuck with an image, a symbol, gave him a nasty feeling of creative claustrophobia,” wrote Barbara Radice, the late maestro’s widow and the only journalist to be a member of Memphis, in her 1993 book, Ettore Sottsass: A Critical Biography. Just five years after the spectacular coming-out party, the designer rejected Memphis and turned his attention to Sottsass Associati, his architecture practice, where he continued to collaborate with many of the same young upstarts. But despite Sottsass’s best efforts, the design world never quite shook the image.

This year, with the celebration of Sottsass’s centennial, several exhibitions aim to deepen the architect’s legacy by surveying his prolific practice and illuminating his important early works, his inspirations, and the type of revolutionary thinking that predated Memphis. “To judge Sottsass on Memphis alone is like judging Robert De Niro on the movie Meet the Fockers,” quips Marc Benda, whose New York gallery, Friedman Benda, represents Sottsass and hosted the final show of his work in 2007, just three months before his death. “You’d be missing many of his investigations into ceramics, his accomplishments as an industrial designer, and his substantial work in glass.”

Karl Lagerfeld's Monte Carlo apartment in the early 1980s. Outfitted entirely in Memphis, it featured Sottsass's Carlton room divider and two light fixtures.

THE SON OF AN ARCHITECT, Sottsass, who was born in Austria and educated in Turin, set up his own design practice after returning from World War II. He began experimenting with ceramics in 1956, when Irving Richards, a shop owner on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, asked him to create a series of vessels “in the modern style.” While the collection fell short of commercial success—Sottsass hadn’t given much thought to the functional purpose of the objects—the architect continued working in the medium until his death, often producing his designs with the Italian firm Bitossi Ceramiche.

“He built his formal language with ceramics,” says Paris-based designer Charles Zana, who began collecting Sottsass’s work in the 1990s. In May, during the Venice Biennale, Zana mounted a show of 70 Sottsass ceramics in Carlo Scarpa’s recently restored Olivetti showroom, where the designer’s iconoclastic calculators and typewriters still line the shelves. Many of the pieces in the show—particularly a six-foot-tall totem he imagined in Palo Alto, California, in 1964—reference ancient architectural forms and ritual objects, constant sources of inspiration for Sottsass that would influence the shapes and structures of Memphis designs decades later. After all, while the group arbitrarily adopted its name from the lyrics of a Bob Dylan song, it’s no accident that the moniker also nods to the ancient Egyptian city.

Long before the Carlton room divider enraptured aficionados of avant-garde design, Sottsass spent years playing with radical forms and materials in his furniture, always questioning traditional ideas of functionality. In 1956, when the Florentine furniture maker Poltronova brought Sottsass on as a consultant, he began experimenting with cartoonish cabinets in wood and plastic laminate. Some of the most notable designs from that era were his 1960s superboxes—massive case pieces meant to hold all of one’s belongings and be placed, like a menhir, in the center of a room—that radiated Memphis brio fully 15 years avant la lettre . One of these will star in a wide-ranging exhibition of Sottsass’s work set to open at the Met Breuer in New York in July.

“Even people familiar with design tend to equate Sottsass with Memphis, which they’ve written off as not their taste, or simply bad taste,” says Christian Larsen, the associate curator of modern decorative arts and design at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who is organizing the show. “In truth, his work was constantly developing. He was always looking to the next thing.” Larsen will explore Sottsass’s varied influences by juxtaposing his work with pieces from the Met’s collection: Indian ritual objects next to Sottsass’s ceramic totems; Egyptian jewelry alongside his earrings and necklaces.

More shows celebrated Sottsass’s less-familiar creations throughout the spring. In April, Le Stanze del Vetro, a museum in Venice, unveiled an exhibition of some 200 glass works, many of them created in the 1990s and early 2000s, just before the end of his life. In June, Benda will bring a cabinet from a private collection that hasn’t been exhibited in more than 50 years to Switzerland for Design Miami/Basel. Each of these shows, in one way or another, argues for a fuller appreciation of Sottsass’s oeuvre and his place in design history. As Larsen puts it, “You might know Memphis first and Sottsass second, and that’s what needs to change.”

Leave a Reply