On first glance, Ryan Neil doesn’t appear to fit the mold of a bonsai master. He’s young, American, and buff, with the boyish good looks of a Tom Brady. But appearances can be deceiving. Neil, who grew up in Colorado and first discovered bonsai at a county fair, began his first internship at age 12, studied horticulture at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, then apprenticed under the legendary Masahiko Kimura in Japan. The rugged trees of the Wild West eventually beckoned him back, and he opened Bonsai Mirai in Oregon in 2010. Since then, he’s become one of the most respected bonsai artists of our day, racking up a discerning clientele and having his work exhibited at institutions like the Portland Art Museum .

I sat down with Neil to get to the root of all things bonsai, including the high prices his trees command.

Architectural Digest: You grew up in Colorado, which isn’t the first place that springs to mind when you think bonsai. How were you exposed to this discipline?

Ryan Neil: When I was 12, I was at a county fair and I saw people buying bonsai trees from a booth. I was like, Oh my gosh, normal people can do this! So I went to the library and checked out every book I could find about it. I found [my future master] Mr Kimura's work in a magazine and it was pretty immediate for me. He gave such a human quality to his trees, so from that point on, my goal was just getting to his nursery to apprentice under him.

Neil on the grounds of Bonsai Mirai.

AD: Which you eventually did.

RN: Yes, but my research first led me to a gentleman in Denver named Harold Sasaki, who had a bonsai nursery. He was working primarily with stunted and dwarfed trees that he was collecting out of the Rocky Mountains. That was my first exposure to material that was 200 to 500 years old and that was naturally dwarfed because it grows in the rock in a confined environment. [Sasaki] was someone who knew how to extract those faithfully, respectfully, and responsibly, and then knew how to manipulate them and create these beautiful forms. I started studying with him one day a month. I would drive three hours over the Rockies on Wednesdays after school and hang with him. Then I would drive home.

After that I went to Japan and apprenticed with Mr. Kimura, who is considered the father of modern bonsai. He really changed the face of what bonsai was as a traditional endeavor, and turned it into the very innovative, artistic endeavor that the world looks at it as now. I should [qualify] that I’m not superpassionate about Asian culture. I didn’t go to Japan because I love Japan. I went to Japan because I love the bonsai and that was the best place to learn about it.

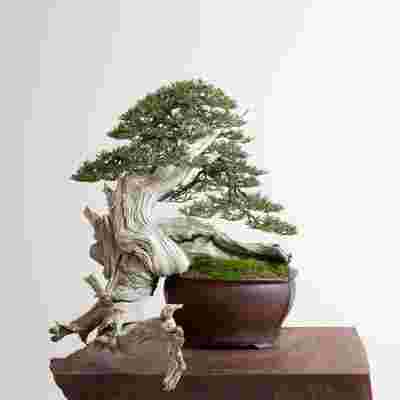

Limber Pine.

AD: What is it about bonsai that speaks to you?

RN: As a bonsai geek, I see it as a higher art form and a medium to bring about a bigger discussion about our society, social issues, and our relationship to our environment. Bonsai as an art form and practice is extremely wide open in terms of interpretation. What speaks to me is using these really old trees collected out of rugged environments, and trying to pull on native shapes and quintessential shapes that make those trees identifiable from that region and environment.

AD: Your practice is based in Oregon, outside of Portland. What made you choose that area?

RN: We have trees here at Mirai that are closing in on 2,000 years old. Those are the special cases, but the ballpark range is 200 to 600 years old. These are native species to the western United States. My dad and I started going out into the Rockies when I was in high school, finding material, and collecting it sustainably and responsibly. One of the biggest advantages I had when I went to Japan to apprentice was that I had already started working with trees out of the wild. I wasn’t going there to learn the Japanese approach to bonsai, which is a fairly patterned discipline—you’re striving for perfection in pattern. For me, that didn’t represent the American landscape or the species that I had been working with.

Rocky Mountain Juniper.

AD: Do you still collect your own trees?

RN: There’s a whole community around me. We have students from 17 countries and clients in almost every state in the country. I started seeking out people who could collect trees better than I ever could. I started seeking out ceramists and woodworkers who could create the platforms I would be displaying the trees on.

AD: What do you hope to express through your work?

RN: My goal is to create pieces that you can’t just walk by and be ambivalent around. I want somebody to have to respond. Whether they hate it or love it, at least they can’t ignore it. My design ethos is pushing the degree of asymmetry to a point that either evokes an emotion or a discomfort, or an excitement in design energy that forces people to respond and acknowledge the piece. When you push that envelope you obviously have a lot of failure, whether it’s structural failure within the tree or design failure. But by pushing those outer boundaries, I think we’ve been able to refine to a large degree how we exist inside that exploration of creating emotion and energy and design. But also walking that line so we still maintain its integrity. The changes over time that are not within our control—that’s what makes bonsai so special.

Neil pruning one of his bonsai trees.

AD: And how do you determine the value of your trees, which sell for $2,500 to $750,000 each?

RN: I’m actually working with an economics professor at the University of Missouri on whether or not you can develop some sort of algorithm that can compute value based on certain criteria and categories. Those pieces that sell for a really high dollar hold the most value characteristics of that species and possess those in the highest form, and then the design that’s been invested and put into that tree also maximizes its aesthetic capacity to be as engaging and interesting and beautiful as it possibly can. And then the ceramics that hold it also have that same level of investment. We have ceramic containers alone that are $15,000 to $20,000.

AD: What kind of clientele do you have?

RN: Our client list is starting to become extremely exclusive, but inside of that we have to sign nondisclosures. We live in Amazon country, Microsoft country, Nike country, Adidas country, and William Kennedy country, so the client list is pretty rich up here. We also have strong connections in Florida, New York, Texas, and the Bay Area. All of the trees we sell are trees that have to exist outdoors. I have a client that lives in Manhattan in an I.M. Pei building, and he’s got marble shelves that face a mitered-corner glass window. So there are clients that have found situations where they’re capable of cultivating these indoors, but it’s an extremely challenging thing to do. We also end up potentially designing the space in which their trees are held.

Vine Maple.

AD: What’s the difference between bonsai we see in interiors and the ones you do?

RN: Typically, when you see trees inside, those are trees that are tropical in nature, like ficus, schefflera, or trees geared towards lower-light situations. The trees we work on are 180 degrees the opposite. They’re trees that depend on ultrahigh levels of ultraviolet light, like juniper or hemlocks. Those trees need a higher level of light to survive and they also need to experience temperature fluctuations.

AD: There has been a real resurgence in potted plants lately, specifically bonsai and succulents. What would you attribute that to?

I think the movement we’re experiencing is people’s recognition that our connection—or potentially what’s become our disconnection—from the environment is taking us away from an existence and a way of life that we depend on as an epicenter for connectivity and health. So as opposed to working with something that’s ultimate future is going to be limited and terminated [like cut flowers], the desire to cooperate and play a role in the existence of this continually evolving living piece of art is appealing. Also, I think there’s a reassessment and people are starting to consider how we make our immediate environment a space where we’re able to reach a better equilibrium in life. And I think one of the key pillars is the cultivation of these very quiet, nonresponsive, nonrapid, moving, living things that still give you feedback, allow you to engage, and just slow down for a minute.

The whole idea of cultivating something is not to minimize your role in that relationship, but to maximize what that role in the relationship provides—that obligation to another living thing.

Leave a Reply