Imagine being a young architect, close to finishing your first solo project. Only it’s no standard building, and in no ordinary location. It’s a six-story, 10-bedroom villa called Villa Punto de Vista , in a spectacular tropical rainforest beside the sea in Costa Rica. That young architect was me.

In truth, I was in way over my head. Sure, I had worked on challenging projects with my previous firm, Gensler . But this building would prove to be a different kind of beast. The madness began after I received a phone call from my brother, Christien, who worked for a luxury travel agency. “Great news," he said. "I may have a client for the villa for New Year’s week. How’s the project coming?” My heart sank. More than two years in, and we were nearly out of money. We really could have benefited from a holiday rental. But there was no way we could be ready in time, I told him. “But it’s apparently a famous person,” my brother added. “Some architect,” he told me. “His name is I. M. Pei. Ever heard of him?” My brother was not a student of architecture, so the significance of this was lost on him.

I almost dropped the phone. The I. M. Pei ? The last living father of modern architecture? The master of geometric form, technical transparency, and poetic landscape? Designer of the Louvre addition, with its pyramidal simplicity, arguably the most iconic architectural project in the world? Years later, I still can't believe my next words: “We’ll be ready,” I assured Christien. If that wasn't reckless optimism, then I don't know what is.

Thus began the most difficult two and a half months of my career—and likely my life. At the time, the villa was less a building nearing completion than a messy construction project. The ballroom had no floor. The pool was still being poured. The elevator pit was leaking from a mysterious source, and the leak was holding up the elevator installation. And those were only a few items from a lengthy list.

The pressure was enormous. And while I did my best to convey to my workers the significance of our first guest, they simply had no idea about Mr. Pei’s place in the architectural firmament. I pushed them hard, and keeping up morale during 12- to 18-hour workdays became one of my biggest challenges. The final, frantic days and sleepless nights before Mr. Pei’s arrival made my all-nighters in architecture school seem like nursery school by comparison. But our team ultimately rose to the occasion. It wasn’t perfect, but we were ready.

Another angle shows Villa Punto de Vista at dusk.

A chauffeured Mercedes-Benz van pulled up to our villa, carrying our esteemed—and very first—guest. Within minutes, I. M. Pei was resting in a teakwood chair in the ballroom. He didn’t seem to notice that the wood floor had yet to be polished or sealed. Instead, I found him looking about as though he was in a museum. This made me even more nervous and excited as I approached him.

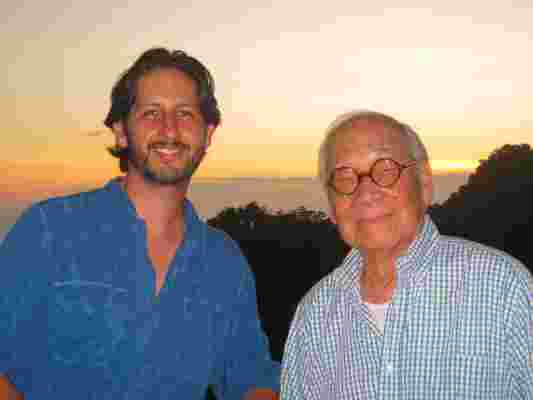

A picture of David Konwiser and the legendary architect I.M. Pei at the Villa Punto de Vista resort in Costa Rica.

Mr. Pei greeted me graciously when I introduced myself as the architect. His manner was quietly confident and he spoke in soliloquies. As he asked specific questions about the villa, I found myself wondering whether he was speaking to me or to himself.

A look at a dining room terrace, which overlooks the Pacific Ocean.

At sunset that first night, Mr. Pei said, “David, tell me, what is it about this building that makes you most proud?” I led him to the column-free, mitered glass corner under the Jacuzzi on the roof deck. From this panoramic perch on the villa’s fifth floor, I focused his attention on the three very pronounced, cantilevered terraces of two of the villa’s bedrooms and the protruding events terrace. I said, “There’s not a corner in the villa that isn’t a floating cantilever.” Mr. Pei turned, smiled, and said something I’ll remember as long as I live: “David, it’s a real tour de force.”

Konwiser is most proud of the fact that there isn't a corner in the villa that is not a floating cantilever, a point he explained to Pei during the visit.

It all went too fast. In the heat of the moment, I neglected to ask him the sort of questions that any architect might ask such a legend: What’s your design process? How do you know you have achieved the right solution? Instead, we spoke mostly about classical music and nature, which he explained were two lifelong sources of inspiration.

“You know, those long cantilevers were designed to the Second Movement of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2," I said. His eyes lit up, and he looked at me and nodded in a way that implied he could not only envision my design process, but that he could relate to it. That, to me, might have been the greatest compliment of all.

Leave a Reply